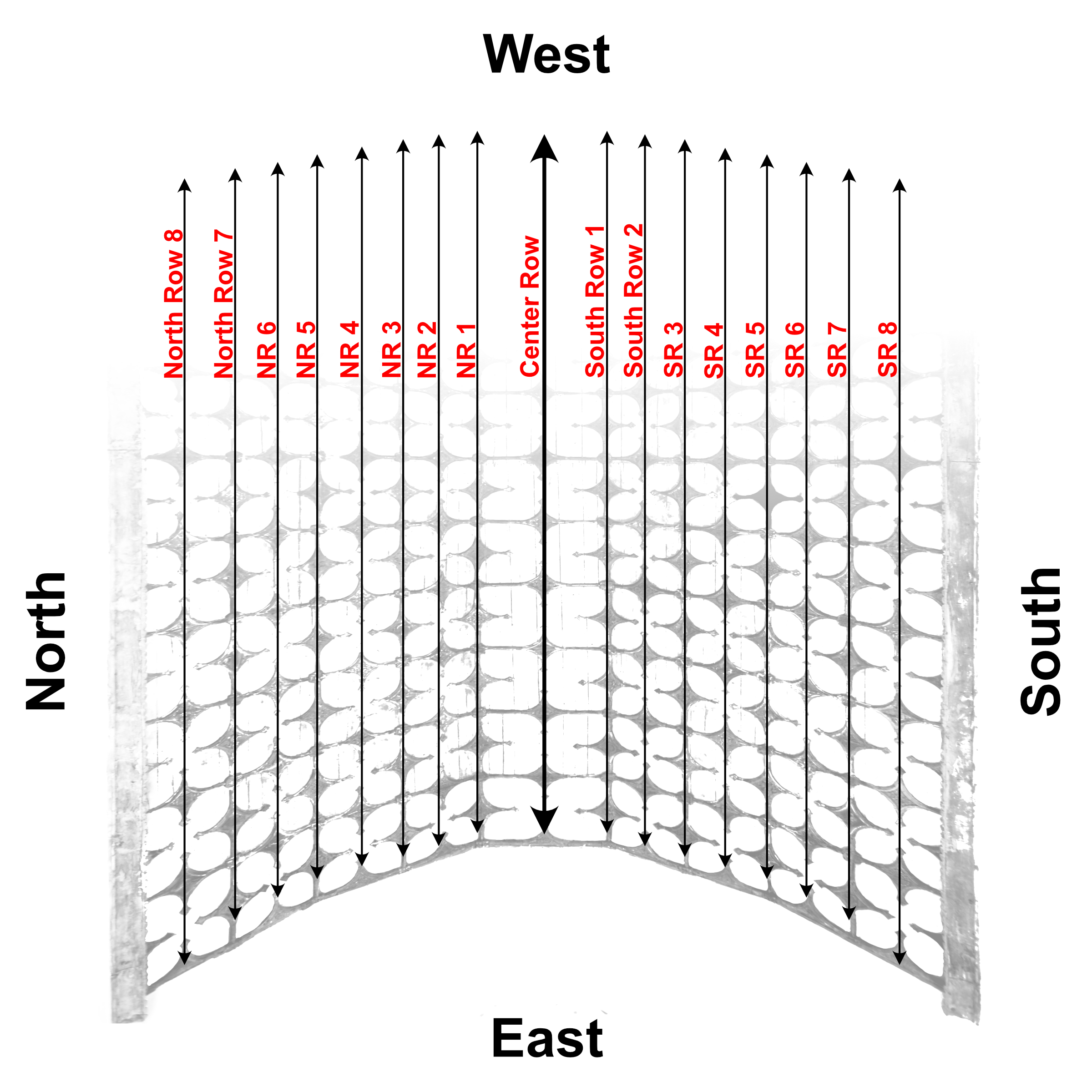

NORTH CEILING

CENTRE CEILING

The Gazeley Ceiling, by Simon Johnson

(author of the book about the Gazeley Ceiling, “Men, Myths and Monsters”- see tab “The Book”).

I live in Aotearoa New Zealand, where our oldest surviving building was completed in 1822. Perhaps this is what drew me to Britain’s medieval churches, and more specifically, the imagery they contain. Distant cultures are mysterious, and art is as important in understanding them as written records.

So on my visits to East Anglia I would always bring a camera, telephoto lens and sturdy tripod. These opened a world in which sacred and profane subjects sat side by side and all manner of incongruous things were going on. Grotesque faces peer from a carved screen containing painted panels of saints, and a row of wooden angels share a nave roof with a doctor examining a urine flask and a mermaid holding a mirror and comb.

Fool with bagpipe, All Saints, Elm, 15th century. The figure stands out in strong relief and details such as the bells on his costume are crisply executed.

Gazeley beast head. Details such as the eye and mane are only incised into the surface, so that the image is difficult to identify except at close range. All of the panels have been made from two pieces of wood joined in the centre which have shrunk over the years. Many as in this example have white-grey stains which are the result of roof leaks.

I first came to All Saints Gazeley in 2018. I had been told that there was a carving of a bared backside on the chancel roof and was keen to photograph it. At first it was difficult to see anything apart from a linked pattern of panels rather like a patchwork quilt. Through the telephoto lens it was a different story. The panels were carved with farm animals, angels playing instruments, mythical beasts, birds and human faces.

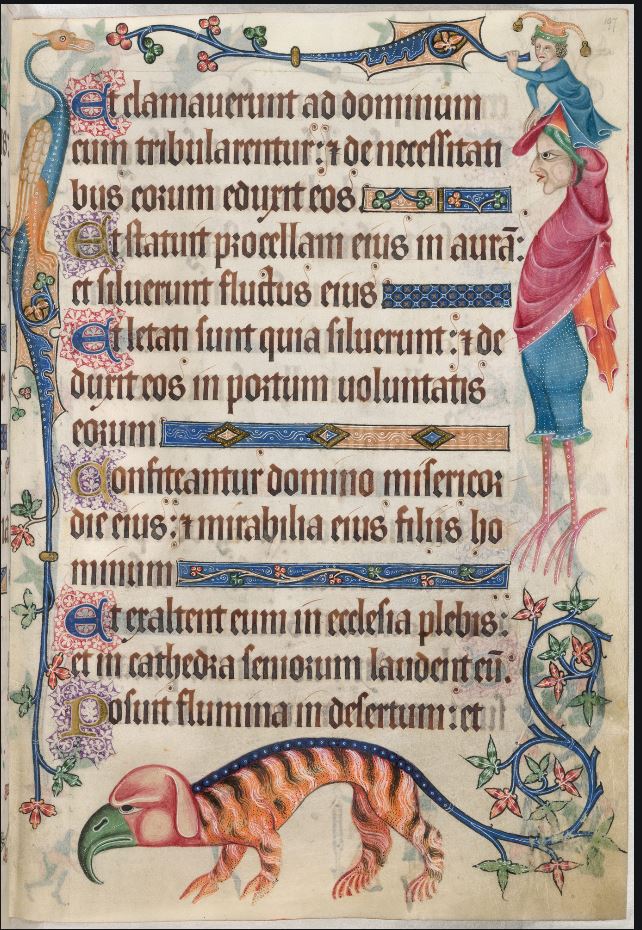

Some of the images were common to many medieval churches. A fox carries off a goose, a reminder that the Devil is always waiting to pounce on anyone foolish enough to listen to him. There is an Agnus Dei, and several dragons. But many of All Saints’ Gazeley’s carvings are very unusual, perhaps unique. One panel shows a sciapod, a big-footed humanoid believed to live in Ethiopia. Wild men were not uncommon subjects for medieval artists, and invariably carry a mighty club which looks like an uprooted sapling. Gazeley’s chancel roof has three panels with carvings of wild men, who are suitably solid and hairy. But two of them carry harps, inverting the viewer’s expectations. Turning the world upside down was a common device in medieval humour and even today we get the joke.

Gazeley’s other rarities are a dragonfly, and a hand grasping the feet of a bird. Insects are quite common decorations in the marginalia of manuscripts but not in church carvings. The trapped bird is a mystery. It may be intended as a moral lesson, or simply show a fowler plucking a bird from his net. Questions like this remind us why Gazeley’s chancel roof must be preserved. It is a precious record of medieval life and culture, an irreplaceable historical resource.

Simon Johnson, 2024

Illuminated page from the Luttrell Psalter